| |

Interview: Professor Paul von Ragué Schleyer

Interviewed March 28, 2006

Professor Paul Schleyer is the Graham Perdue Professor of Chemistry at the University of Georgia, where he has been for the past 8 years. Prior to that, he was a professor at the University at Erlangen (co-director of the Organic Institute) and the founding director of its Computer Chemistry Center. Schleyer began his academic career at Princeton University.

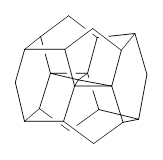

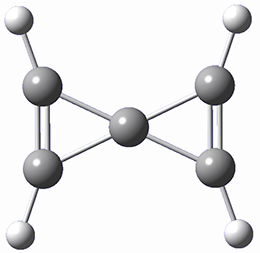

Professor Schleyer’s involvement in computational chemistry dates back to the 1960s, when his group was performing MM and semi-empirical computations as an adjunct to his predominantly experimental research program. This situation dramatically changed when Professor John Pople invited Schleyer to visit Carnegie-Mellon University in 1969 as the NSF Center of Excellence Lecturer. From discussions with Dr. Pople, it became clear to Schleyer that “ab initio methods could look at controversial subjects like the nonclassical carbocations. I became hooked on it!” The collaboration between Pople and Schleyer that originated from that visit lasted well over 20 years, and covered such topics as substituent effects, unusual structures that Schleyer terms “rule-breaking”, and organolithium chemistry. This collaboration started while Schleyer was at Princeton but continued after his move to Erlangen, where Pople came to visit many times. The collaboration was certainly of peers. “It would be unfair to say that the ideas came from me, but it’s clear that the projects we worked on would not have been chosen by Pople. Pople added a great deal of insight and he would advise me on what was computationally possible,” Schleyer recalls of this fruitful relationship.

Schleyer quickly became enamored with the power of ab initio computations to tackle interesting organic problems. His enthusiasm for computational chemistry eventually led to his decision to move to Erlangen – they offered unlimited (24/7) computer time, while Princeton’s counteroffer was just 2 hours of computer time per week. He left Erlangen in 1998 due to enforced retirement. However, his adjunct status at the University of Georgia allowed for a smooth transition back to the United States, where he now enjoys a very productive collaborative relationship with Professor Fritz Schaefer.

Perhaps the problem that best represents how Schleyer exploits the power of ab initio computational chemistry is the question of how to define and measure aromaticity. Schleyer’s interest in the concept of aromaticity spans his entire career. He was drawn to this problem because of the pervasive nature of aromaticity across organic chemistry. Schleyer describes his motivation: “Aromaticity is a central theme of organic chemistry. It is re-examined by each generation of chemists. Changing technology permits that re-examination to occur.” His direct involvement came about by Kutzelnigg’s development of a computer code to calculate chemical shifts. Schleyer began use of this program in the 1980s and applied it first to structural problems. His group “discovered in this manner many experimental structures that were incorrect.”

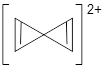

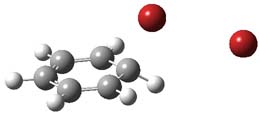

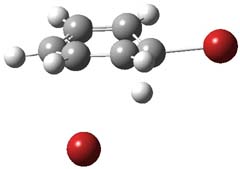

To assess aromaticity, Schleyer first computed the lithium chemical shifts in complexes formed between lithium cation and the hydrocarbon of interest. The lithium cation would typically reside above the aromatic ring and its chemical shift would be affected by the magnetic field of the ring. While this met with some success, Schleyer was frustrated by the fact that lithium was often not positioned especially near the ring, let alone in the center of the ring. This led to the development of nucleus-independent chemical shift (NICS), where the virtual chemical shift can be computed at any point in space. Schleyer advocated using the geometric center of the ring, then later a point 1 Å above the ring center.

Over time, Schleyer came to refine the use of NICS, advocating an examination of NICS values on a grid of points. His most recent paper posits using just the component of the chemical shift tensor perpendicular to the ring evaluated at the center of the ring. This evolution reflects Schleyer’s continuing pursuit of a simple measure of aromaticity. “Our endeavor from the beginning was to select one NICS point that we could say characterizes the compound,” Schleyer says. “The problem is that chemists want a number which they can associate with a phenomenon rather than a picture. The problem with NICS was that it was not soundly based conceptually from the beginning because cyclic electron delocalization-induced ring current was not expressed solely perpendicular to the ring. It’s only that component which is related to aromaticity.”

The majority of our discussion revolved around the definition of aromaticity. Schleyer argues that “aromaticity can be defined perfectly well. It is the manifestation of cyclic electron delocalization which is expressed in various ways. The problem with aromaticity comes in its quantitative definition. How big is the aromaticity of a particular molecule? We can answer this using some properties. One of my objectives is to see whether these various quantities are related to one another. That, I think, is still an open question.”

Schleyer further detailed this thought, “The difficulty in writing about aromaticity is that it is encrusted by two centuries of tradition, which you cannot avoid. You have to stress the interplay of the phenomena. Energetic properties are most important, but you need to keep in mind that aromaticity is only 5% of the total energy. But if you want to get as close to the phenomenon as possible, then one has to go to the property most closely related, which is magnetic properties.” This is why he focuses upon the use of NICS as an aromaticity measure. He is quite confident in his new NICS measure employing the perpendicular component of the chemical shift tensor. “This new criteria is very satisfactory,” he says. “Most people who propose alternative measures do not do the careful step of evaluating them against some basic standard. We evaluate against aromatic stabilization energies.”

Schleyer notes that his evaluation of the aromatic stabilization energy of benzene is larger than many other estimates. This results from the fact that, in his opinion, “all traditional equations for its determination use tainted molecules. Cyclohexene is tainted by hyperconjugation of about 10 kcal mol-1. Even cyclohexane is very tainted, in this case by 1,3-interactions.” An analogous complaint can be made about the methods Schleyer himself employs: NICS is evaluated at some arbitrary point or arbitrary set of points, the block-diagonalized “cyclohexatriene” molecule is a gedanken molecule. When pressed on what then to use as a reference that is not ‘tainted’, Schleyer made this trenchant comment: “What we are trying to measure is virtual. Aromaticity, like almost all concepts in organic chemistry, is virtual. They’re not measurable. You can’t measure atomic charges within a molecule. Hyperconjugation, electronegativity, everything is in this sort of virtual category. Chemists live in a virtual world. But science moves to higher degrees of refinement.” Despite its inherent ‘virtual’ nature, “Aromaticity has this 200 year history. Chemists are interested in the unusual stability and reactivity associated with aromatic molecules. The term survives, and remains an enormously fruitful area of research.”

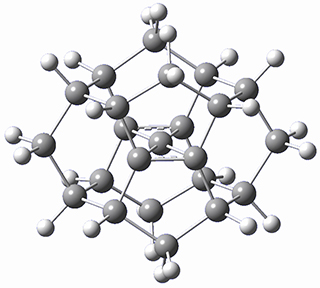

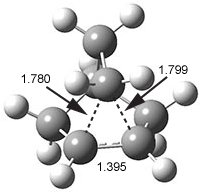

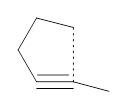

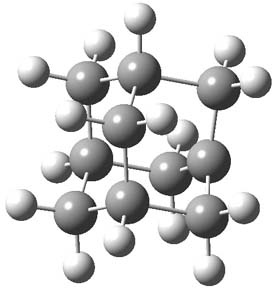

His interest in the annulenes is a natural extension of the quest for understanding aromaticity. Schleyer was particularly drawn to [18]-annulene because it can express the same D6h symmetry as does benzene. His computed chemical shifts for the D6h structure differed significantly from the experimental values, indicating that the structure was clearly wrong. “It was an amazing computational exercise,” Schleyer mused, “because practically every level you used to optimize the geometry gave a different structure. MP2 overshot the aromaticity, HF and B3LYP undershot it. Empirically, we had to find a level that worked. This was not very intellectually satisfying but was a pragmatic solution.” Schleyer expected a lot of flak from crystallographers about this result, but in fact none occurred. He hopes that the x-ray structure will be re-done at some point.

Reflecting on the progress of computational chemistry, Schleyer recalls that “physical organic chemists were actually antagonistic toward computational chemistry at the beginning. One of my friends said that he thought I had gone mad. In addition, most theoreticians disdained me as a black-box user.” In those early years as a computational chemist, Schleyer felt disenfranchised from the physical organic chemistry community. Only slowly has he felt accepted back into this camp. “Physical organic chemists have adopted computational chemistry; perhaps, I hope to think, due to my example demonstrating what can be done. If you can show people that you can compute chemical properties, like chemical shifts to an accuracy that is useful, computed structures that are better than experiment, then they get the word sooner or later that maybe you’d better do some calculations.” In fact, Schleyer considers this to be his greatest contribution to science – demonstrating by his own example the importance of computational chemistry towards solving relevant chemical problems. He cites his role in helping to establish the Journal of Computational Chemistry in both giving name to the discipline and stature to its practitioners.

Schleyer looks to the future of computational chemistry residing in the breadth of the periodic table. “Computational work has concentrated on one element, namely carbon,” Schleyer says. “The rest of the periodic table is waiting to be explored.” On the other hand, he is dismayed by the state of research at universities. In his opinion, “the function of universities is to do pure research, not to do applied research. Pure research will not be carried out at any other location.” Schleyer sums up his position this way – “Pure research is like putting money in the bank. Applied research is taking the money out.” According to this motto, Schleyer’s account is very much in the black.

Reprinted from Computational Organic Chemistry, Steven M. Bachrach, 2014, Wiley:Hoboken.

|

|