Inverted carbon atoms, where the bonds from a single carbon atom are made to four other atoms which all on one side of a plane, remain a subject of fascination for organic chemists. We simply like to put carbon into unusual environments! Bremer, Fokin, and Schreiner have examined a selection of molecules possessing inverted carbon atoms and highlights some problems both with experiments and computations.1

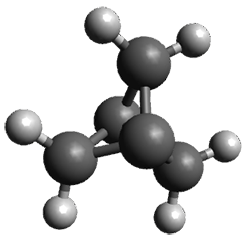

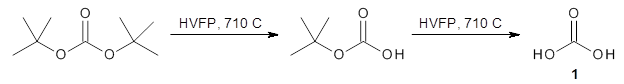

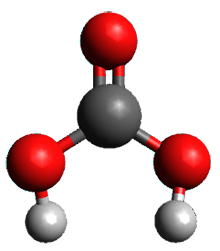

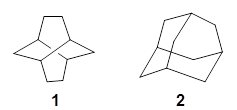

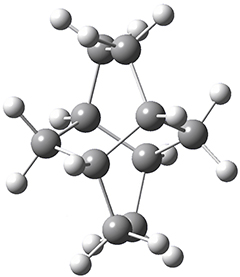

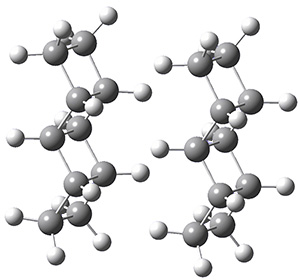

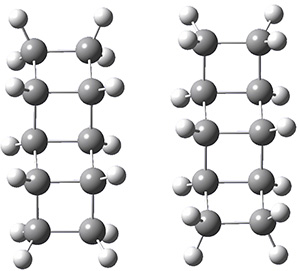

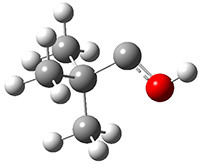

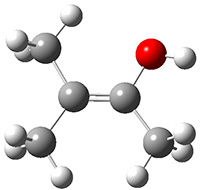

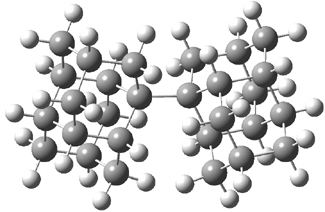

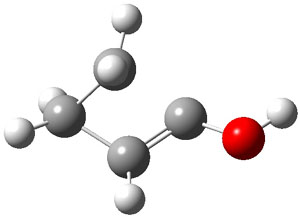

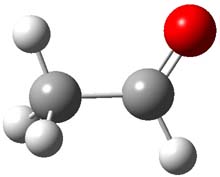

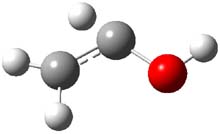

The prototype of the inverted carbon is propellane 1. The Cinv-Cinv bond distance is 1.594 Å as determined in a gas-phase electron diffraction experiment.2 A selection of bond distance computed with various methods is shown in Figure 1. Note that CASPT2/6-31G(d), CCSD(t)/cc-pVTZ and MP2 does a very fine job in predicting the structure. However, a selection of DFT methods predict a distance that is too short, and these methods include functionals that include dispersion corrections or have been designed to account for medium-range electron correlation.

|

CASPT2/6-31G(d) CCSD(T)/cc-pVTZ MP2/cc-pVTZ MP2/cc-pVQZ B3LYP/6-311+G(d,p) B3LYP-D3BJ/6-311+G(d,p) M06-2x/6-311+G(d,p) |

1.596 1.595 1.596 1.590 1.575 1.575 1.550 |

Figure 1. Optimized Structure of 1 at MP2/cc-pVTZ, along with Cinv-Cinv distances (Å) computed with different methods.

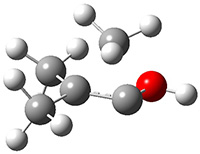

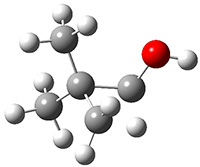

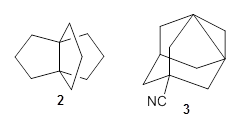

Propellanes without an inverted carbon, like 2, are properly described by these DFT methods; the C-C distance predicted by the DFT methods is close to that predicted by the post-HF methods.

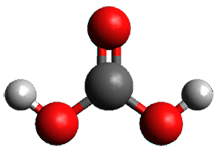

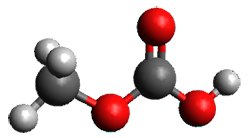

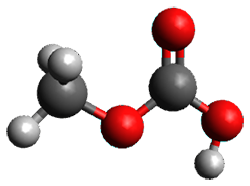

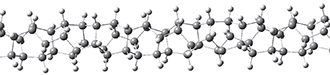

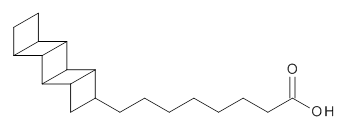

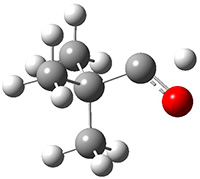

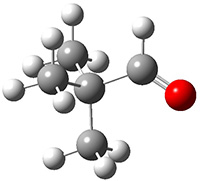

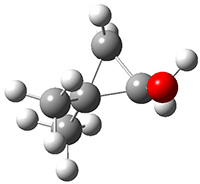

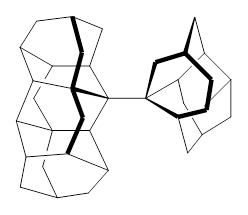

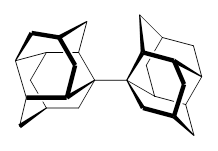

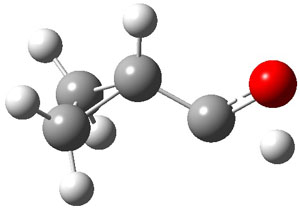

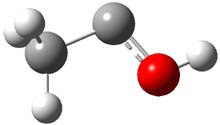

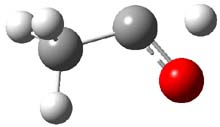

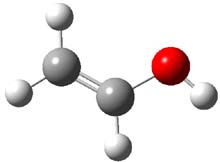

The propellane 3 has been referred to many times for its seemingly very long Cinv-Cinv bond: an x-ray study from 1973 indicates it is 1.643 Å.3 However, this distance is computed at MP2/cc-pVTZ to be considerably shorter: 1.571 Å (Figure 2). Bremer, Fokin, and Schreiner resynthesized 3 and conducted a new x-ray study, and find that the Cinv-Cinv distance is 1.5838 Å, in reasonable agreement with the computation. This is yet another example of where computation has pointed towards experimental errors in chemical structure.

Figure 2. MP2/cc-pVTZ optimized structure of 3.

However, DFT methods fail to properly predict the Cinv-Cinv distance in 3. The functionals B3LYP, B3LYP-D3BJ and M06-2x (with the cc-pVTZ basis set) predict a distance of 1.560, 1.555, and 1.545 Å, respectively. Bremer, Folkin and Schreiner did not consider the ωB97X-D functional, so I optimized the structure of 3 at ωB97X-D/cc-pVTZ and the distance is 1.546 Å.

Inverted carbon atoms appear to be a significant challenge for DFT methods.

References

(1) Bremer, M.; Untenecker, H.; Gunchenko, P. A.; Fokin, A. A.; Schreiner, P. R. "Inverted Carbon Geometries: Challenges to Experiment and Theory," J. Org. Chem. 2015, 80, 6520–6524, DOI: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b00845.

(2) Hedberg, L.; Hedberg, K. "The molecular structure of gaseous [1.1.1]propellane: an electron-diffraction investigation," J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985, 107, 7257-7260, DOI: 10.1021/ja00311a004.

(3) Gibbons, C. S.; Trotter, J. "Crystal Structure of 1-Cyanotetracyclo[3.3.1.13,7.03,7]decane," Can. J. Chem. 1973, 51, 87-91, DOI: 10.1139/v73-012.

InChIs

1: InChI=1S/C5H6/c1-4-2-5(1,4)3-4/h1-3H2

InChIKey=ZTXSPLGEGCABFL-UHFFFAOYSA-N

3: InChI=1S/C11H13N/c12-7-9-1-8-2-10(4-9)6-11(10,3-8)5-9/h8H,1-6H2

InChIKey=KTXBGPGYWQAZAS-UHFFFAOYSA-N