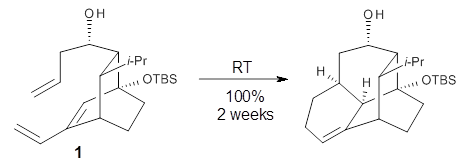

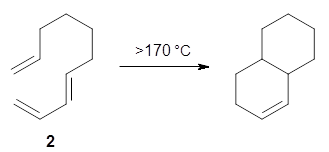

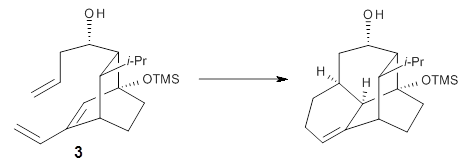

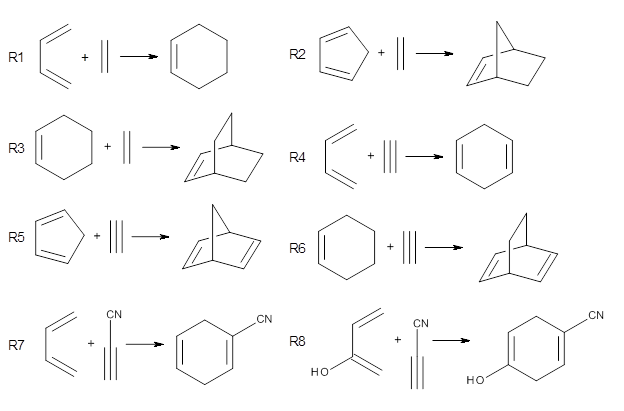

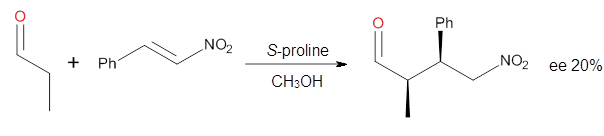

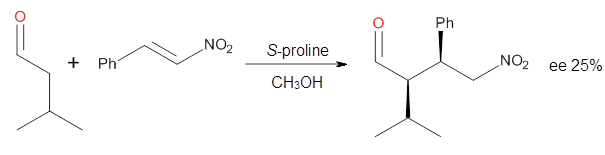

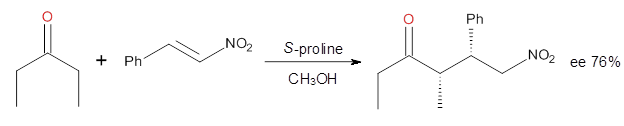

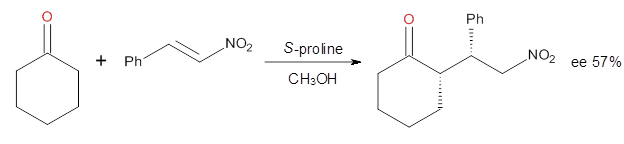

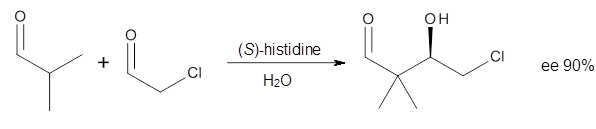

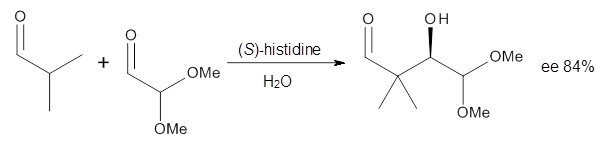

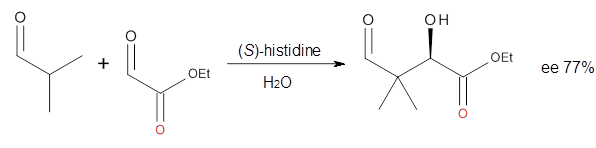

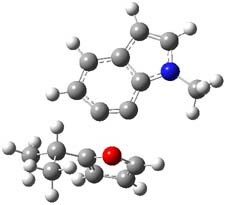

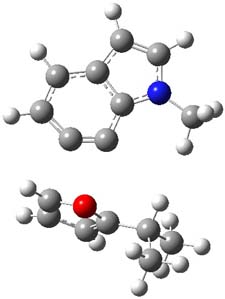

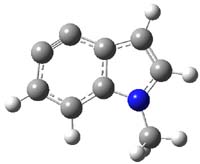

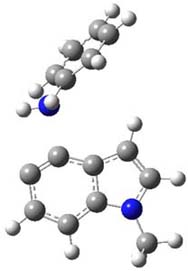

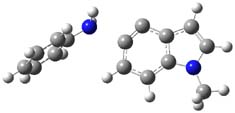

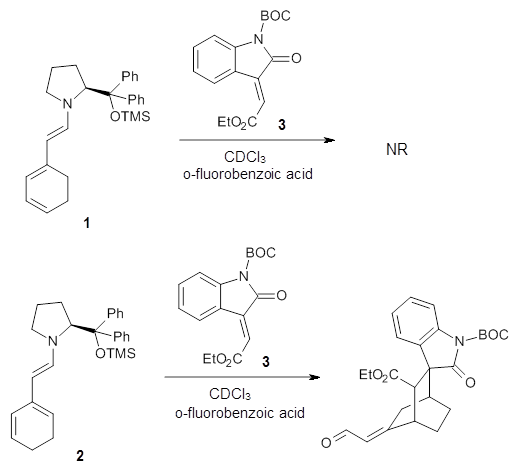

Halskov, et al.1 reported the interesting Diels-Alder selectivity shown in Scheme 1. The linear trienamine 1 did not undergo the Diels-Alder addition, while the less stable cross-conjugated diene 2 does react with 3 with high diastereo- and enantioselectivity. Their MPW1K/6-31+G(d,p) computations on a model system, carried out for a gas-phase environment, indicated a concerted mechanism, with thermodynamic control. However, the barrier for the reverse reaction for the kinetic product was computed to be greater than 30 kcal mol-1, casting doubt on the possibility of thermodynamic control.

Scheme 1.

Houk and co-workers2 have re-examined this reaction with the critical addition of performing the computation including the solvent effects. Since the stepwise alternatives involve the formation of zwitterions, solvent can be critical in stabilizing these charge-separated species, intermediates that might be unstable in the gas phase. Henry Rzepa has pointed out in his blog and on many comments in this blog about the need to include solvent, and this case is a prime example of the problems inherent in neglecting solvation.

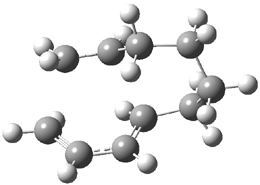

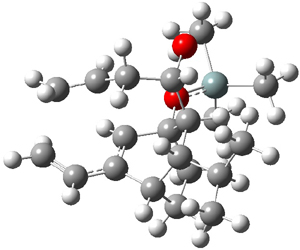

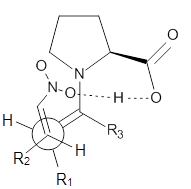

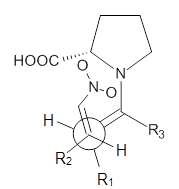

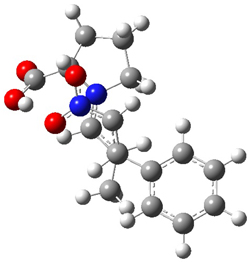

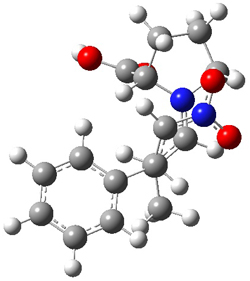

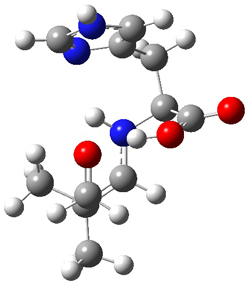

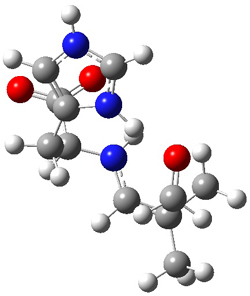

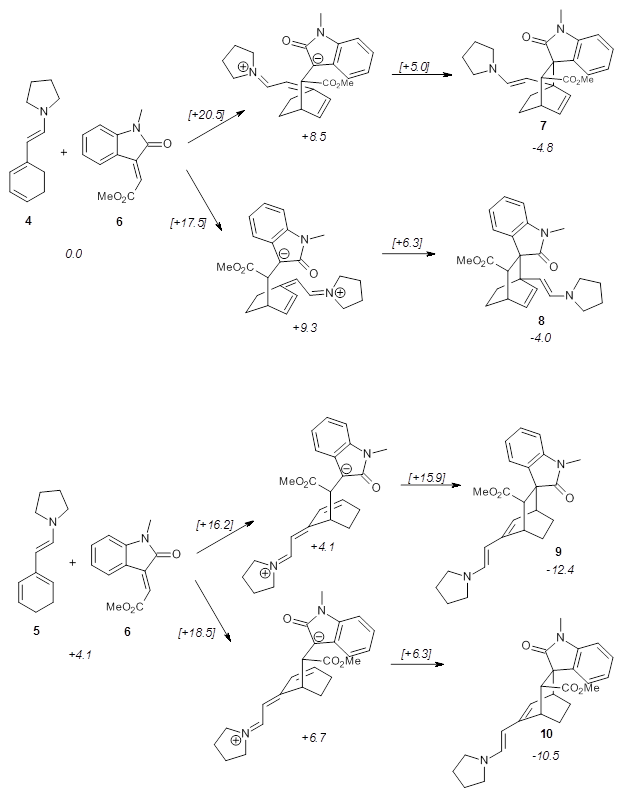

Using models of the above reaction Houk located two zwitterionic intermediates of the Michael addition for both the reactions of 4 with 6 and of 5 with 6. The second step then involves the closure of the ring to give what would be Diels-Alder products. This is shown in Scheme 2. They were unable to locate transition states for any concerted pathways. The computations were done at M06-2x/def2-TZVPP/IEFPCM//B97D/6-31+G(d,p)/IEFPCM, modeling trichloromethane as the solvent.

Scheme 2. Numbers in italics are energies relative to 4 + 6.

The activation barrier for the second step in each reaction is very small, typically less than 5 kcal mol-1, so the first step is rate determining. The lowest barrier is for the reaction of 5 leading to 9, analogous to the observed product. Furthermore, 9 is also the thermodynamic product. Thus, the regioselectivity is both kinetically and thermodynamically controlled through a stepwise reaction. This conclusion is only possible by including solvent in order to stabilize the zwitterionic intermediates, and should be a word of caution for everyone doing computations: be sure to include solvent for any reactions that involved charged or charge-separated species at any point along the reaction pathway!

References

(1) Halskov, K. S.; Johansen, T. K.; Davis, R. L.; Steurer, M.; Jensen, F.; Jørgensen, K. A. "Cross-trienamines in Asymmetric Organocatalysis," J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12943-12946,

DOI: 10.1021/ja3068269.

(2) Dieckmann, A.; Breugst, M.; Houk, K. N. "Zwitterions and Unobserved Intermediates in Organocatalytic Diels–Alder Reactions of Linear and Cross-Conjugated Trienamines," J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 3237-3242, DOI: 10.1021/ja312043g.